Grammar Was Meant to Explain Language — Not Teach It

- Talhah

- Jan 29

- 2 min read

Grammar was never designed to create speakers.

It was designed to analyse speakers who already existed.

This is a detail most learners never hear — and once you see it, you can’t unsee it. Historically, grammar emerged after languages were already being spoken fluently for generations. Scholars didn’t invent grammar rules and then hand them to people. They observed how people naturally spoke… and wrote descriptions of what they noticed.

In other words: Grammar is a report, not an instruction manual.

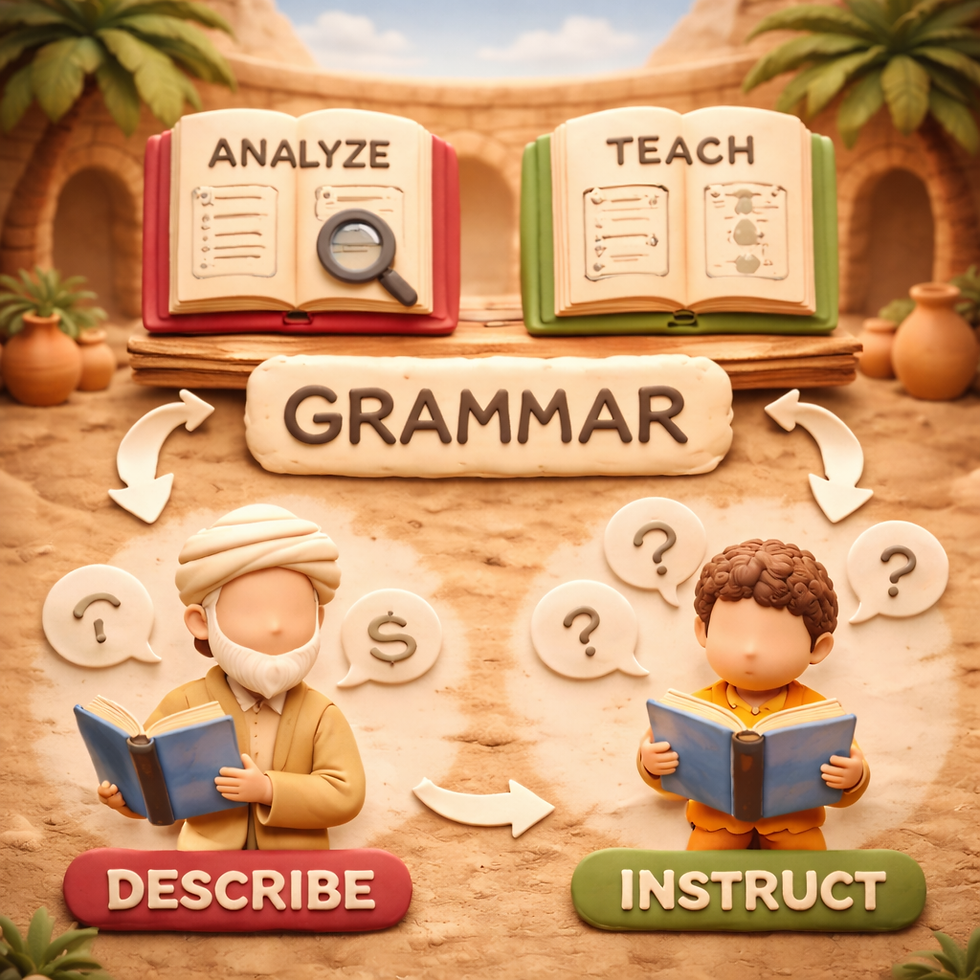

Linguists call this the difference between descriptive grammar and prescriptive grammar.

Descriptive grammar explains how language is actually used

Prescriptive grammar tells people how they should use it

Modern language education flipped these roles — and that flip is where many learners get stuck. There’s strong evidence behind this.

Studies in second-language acquisition show that explicit grammar instruction accounts for only around 5–15% of overall language competence, while the majority comes from input, exposure, and pattern recognition. One well-known meta-analysis by linguist Stephen Krashen found that learners who focused heavily on grammar rules often performed worse in spontaneous communication than learners who focused on understanding meaning first.

Why?

Because grammar knowledge lives in a different part of the brain than fluent language use. You can know a rule and still freeze when speaking. You can explain a structure and still not recognise it in real conversation. That’s because grammar is declarative knowledge (facts you can explain), while fluency is procedural knowledge(skills you can perform). And skills are not built through explanation — they’re built through exposure and repetition.

This is why native speakers often can’t explain their own grammar rules…yet speak flawlessly. They didn’t learn grammar to speak. They spoke — and grammar came later.

When grammar is introduced after familiarity, it suddenly makes sense. It becomes a helpful label, not a burden. A clarification, not a starting point. A tool to explain what you already understand,not a gate you must pass through before you’re allowed to understand anything at all.

And when grammar is used this way, something powerful happens: Instead of slowing you down,it quietly locks in what your brain has already learned naturally.

That’s not avoiding grammar. That’s using it the way it was originally intended.

Comments